This Campaign Brief outlines the current situation regarding the criminalisation of suicide and the rationale for change towards improved efforts on the prevention of suicides and the provision of care for those impacted by suicide.

The Brief is intended to inform advocates and interested parties within countries, governments, organisations and communities, to inspire them to participate in a movement to Decriminalise Suicide Worldwide.

This Brief also acknowledges the significant and important work undertaken by peers and colleagues within the World Health Organisation and its most recent statement on suicide prevention; the International Association of Suicide Prevention, specifically through its ongoing expert Special Interest Groups and the consistent inclusion of suicide decriminalisation as part of its suicide prevention mission; and United for Global Mental Health, notably their 2021 report “Decriminalising Suicide: Saving Lives, Reducing Stigma”; and IASP and United for convening a specialist decimalisation chapter with the Global Mental Health Action Network.

This Campaign Brief seeks to add new dimensions to their work and the findings and should be read in addition to the informed body of work developed by these and other leading global organisations.

Acknowledgements

LifeLine International acknowledges the contributions to this Campaign Brief received from academics, experts, people with lived experience of suicidal crisis and loss, and service providers, including those from its Members in 25 countries.

Various news articles and other publicly available sources have also informed the development of this Brief.

In addition, under the auspices of a joint LifeLine International-LawAsia-International Bar Association Human Rights Law Committee project, this Brief has benefited from the expertise of the following lawyers: Melinda Taylor, Mohamed Youssef, Kelsey Ryan, Fitry Nabiilah, Ian Teh, Justice Anthony Gafoor, and Enie Elive.

Executive Summary

Suicide is a global public health crisis and one of the leading causes of preventable death worldwide. This Campaign Brief takes a comprehensive look at the issue of suicide and crisis, the criminalisation of suicide, the impact on individuals, families and community, and the importance and consequences of its decriminalisation.

Prepared by LifeLine International, the Brief finds that suicide remains criminalised in 25 countries, home to more than 850 million people. Furthermore, the legal status of suicide as a crime remains unclear in 27 others, representing a further population of 370 million people. Criminalisation of suicide attempts is an ineffective deterrent that fails to prevent suicide, creating unnecessary legal frameworks that perpetuate stigma, deters help-seeking behaviour, and inhibits the establishment of crucial crisis support services. Combined, a total population of more than 1.2 billion people live in jurisdictions where suicide is a crime – or its legal status unclear – all of which inhibits help seeking that can save lives. Suicide, everywhere in the world, is preventable.

The global decriminalisation of suicide is therefore vital to promote suicide prevention, access to crisis support services, and ensure the universal right to mental health. In line with the release of this Brief, LifeLine International, a global network with 27 Member providing crisis support services in 23 countries, is launching a groundbreaking campaign, ‘Decriminalise Suicide Worldwide’, to end the criminalisation of suicide. This campaign seeks to offer hope, save lives, and dismantle the barriers preventing help-seeking during a potentially suicidal crisis.

This Brief reflects LifeLine International's commitment to fostering a global movement that prioritises compassion, understanding, and suicide prevention and crisis support over punishment, with the aim of reshaping the world's perspective on suicide. It includes the following key elements:

Global Significance of Suicide as a Public Health Issue:

In the context of our contemporary world, suicide is an alarming and far-reaching public health crisis that demands our immediate and comprehensive attention. It ranks among the leading preventable causes of death on a global scale, touching the lives of individuals, families, workplaces, and entire communities. Its impact is profound and, as a challenge that affects people from all walks of life, regardless of their background, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, it underscores the need for a united and coordinated response.

Complex Nature of Suicidal Crisis:

This Brief fully acknowledges the inherent complexity of a suicidal crisis. Such crises are not singular in their origins but rather arise from a multifaceted interplay of factors, including profound emotional pain and distress. In the context of these crises, individuals grapple with despair and suffering that can quickly overwhelm their ability to cope. As these emotional pressures mount, the possibility of self-harm or even suicide becomes a real consideration for those in crisis. This highlights the immediate necessity of crisis intervention and support for individuals confronting these profound emotional challenges.

Criminalisation of Suicide:

At the heart of LifeLine International’s campaign lies the detrimental consequences of laws and regulatory environments that criminalise suicide attempts. These laws, despite their intentions, are fundamentally counterproductive. Rather than offering a constructive approach to addressing the root causes of suicidal thoughts and behaviours, they inadvertently perpetuate crisis, discrimination and stigma. In doing so, they fail to create an environment where individuals feel safe and supported to reach out for help. The Brief draws attention to the need for a different approach, one that recognises the true nature of this crisis and seeks to offer help rather than punishment.

Historical Roots and the Ineffectiveness of Criminalisation:

A historical perspective on the issue reveals that the criminalisation of suicide often has deep-rooted historical connections, dating back to colonial times, and can also be influenced by religious and cultural factors. However, a modern research landscape offers fresh insights. This contemporary understanding underscores that treating suicide as a crime is largely ineffective in deterring those in crisis. The weight of evidence suggests that the reasons individuals contemplate suicide are not adequately addressed through legal punitive measures. Instead, they point to underlying mental health challenges, personal struggles, and societal pressures as the root causes of such thoughts. This view calls for a shift in our collective approach to the issue, one that centres on compassion, understanding, and support.

The Global Legal Landscape:

Across the world, the legal stance on suicide varies. In 25 countries, suicide attempts are still criminalised, leading at times to unpredictable punitive measures against those in crisis. In addition, a further 27 countries have unclear or uncodified laws, contributing to legal ambiguity and the perpetuation of discrimination, stigma and hurt. In all cases, this leads to a significant reduction in the ability to establish localised crisis support services and acts as major barriers to help seeking behaviours.

Impact on Families and Communities:

The consequences of criminalising suicide extend well beyond the individual in crisis. It casts a long shadow over the lives of their families, friends and communities. This legal framework inadvertently discourages these people from seeking the help they desperately need, creating an environment steeped in fear, secrecy, and stigma. This atmosphere of apprehension makes it also difficult for loved ones to offer the support that could be a lifeline for individuals in crisis. For this reason, the campaign underscores the importance of shifting our approach from one of punishment to one of understanding and care.

Decriminalisation for Improved Suicide Prevention:

The heart of our campaign is the central message of decriminalisation. It underpins a movement that plays a pivotal role in reducing global suicide rates. Decriminalisation is not just about removing legal penalties; it serves as a catalyst for suicide prevention. It strives to eliminate the barriers that prevent individuals in crisis from reaching out and receiving the help they so desperately need. The significance of this shift is not to be underestimated. It is a fundamental step toward reshaping our collective approach to this issue, reducing the immense burden it places on individuals, families, and communities, and ushering in a new era of empathy, understanding, and support.

Global Campaign for Decriminalisation:

LifeLine International spearheads this global campaign, providing vital support to countries where suicide remains criminalised or where its legal status remains uncertain. The central message of this campaign revolves around the belief that mental health is a universal human right. It asserts that individuals in crisis deserve empathy, support, and care, irrespective of their geographic location or personal background. This campaign is a collective endeavour, demonstrating the organisation’s commitment to supporting one another during times of need. It aims to dismantle the stigma surrounding suicide and reshape the global perspective on mental well-being, fostering a world where understanding and support are the cornerstones of our approach to those in crisis.

Campaign Elements:

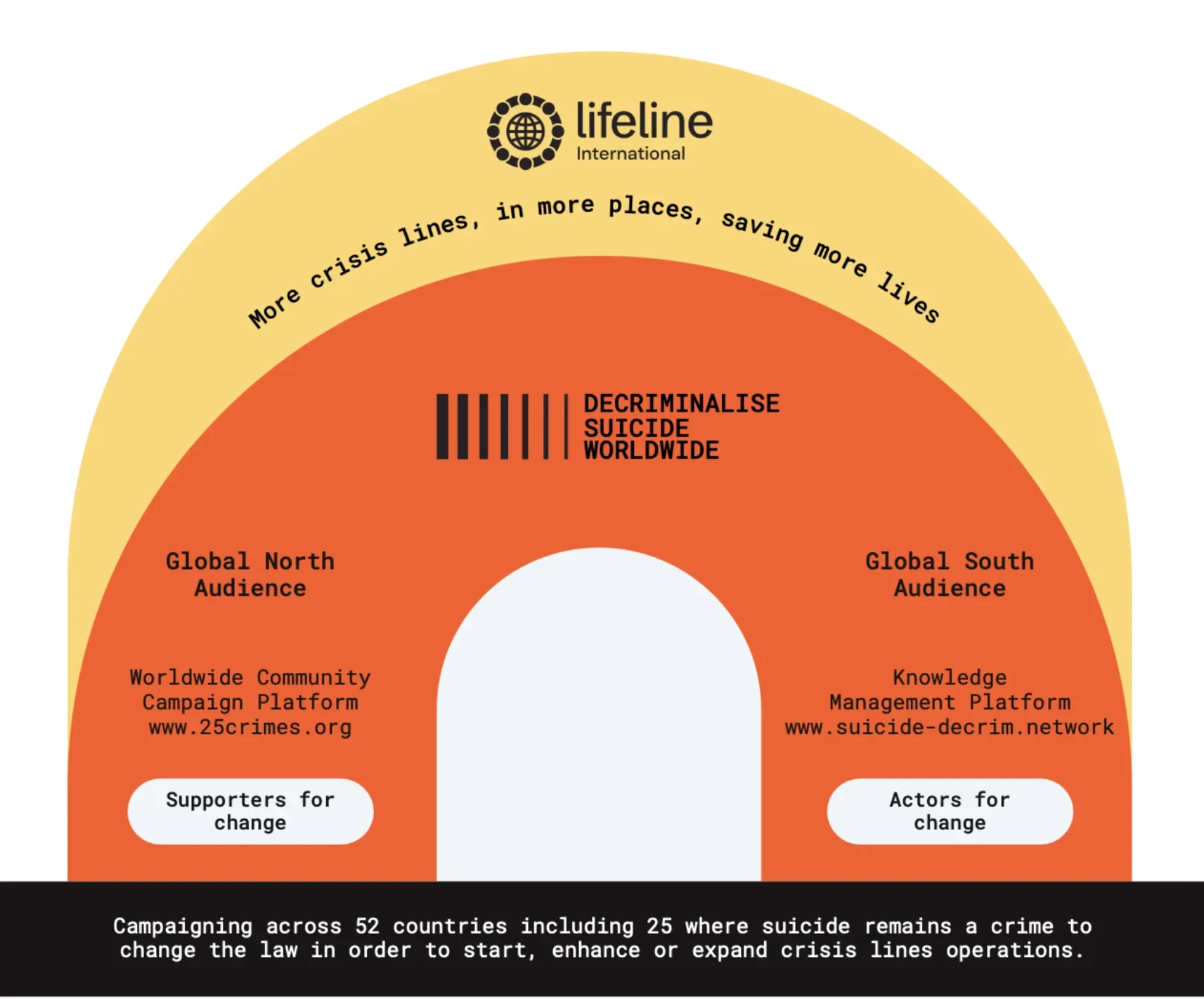

This campaign leverages two primary digital platforms to reach its goals. First, www.25crimes.org functions as a community campaign platform for supporters of change. It empowers individuals with the resources and information they need to advocate for the decriminalisation of suicide on a global scale, yet at a personal and individual level. Second, www.suicide-decrim.network serves as a Knowledge Management Platform for actors for change. LifeLine International will work with actors in the countries where suicide remains a crime, or where the laws are unclear, to support national movements for legislative change and enhanced suicide prevention resources. The platform will deliver tailored materials and information, as well as guides and data sets, pertinent to legislative changes within specific countries. These platforms are instrumental in raising awareness, facilitating advocacy, and promoting understanding of the complex nature of suicide and the need for immediate intervention and support.

This Brief is a call to action, urging individuals worldwide to join the campaign, especially in those countries where suicide remains a crime, or the legal status is uncertain. Through a range of actors and stakeholders, LifeLine International’s campaign will challenge stigma, advocate for change, and ensure that crisis support services are accessible to all. The ultimate goal is to save lives, dismantle the stigma surrounding mental health and suicide prevention, and transform the global landscape of mental well-being.

For an overview of the campaign, please see www.lifeline-international.com/campaign. To join the social movement in support of change, see www.25crimes.org, and for more detailed opportunity to participate as an actor in the campaign, including case studies and actionable steps, please visit www.suicide-decrim.network.

Together, we can build a more empathetic and resilient world, where mental health is truly a universal human right.

Suicide – A Leading Cause of Preventable Death Globally

Suicide is amongst the leading causes of death worldwide and remains a pressing global public health priority. Suicides impact on individuals, families, workplaces, and communities.

Deaths by suicide can be prevented.

One often-overlooked aspect of this problem is the criminalisation of suicide in countries across the globe. Laws that criminalise suicide attempts and their related regulations and practices are counterproductive to the prevention of suicide, as shown in research studies across multiple countries. Suicide rates have been found to be higher in countries which have laws penalising suicide. These laws have far-reaching implications for those in distress, perpetuating stigma and preventing them from accessing the support they need, when they are in a crisis. These laws act as barriers to the provision of life saving services.

Around the world, the criminalisation of suicide remains an alarming reality. From the review of laws, evidence and data performed for this Campaign Brief, approximately 52 countries were identified where suicide is either considered a crime, or the legal framework is unclear, confusing or uncertain. This means around one quarter of countries in the world lack clear legal and regulatory environments that will be conducive to the prevention of suicide.

Our research shows that in the 25 countries where suicide remains a crime, there are over 35,000 annual suicide deaths and over 700,000 attempts.

The roots of criminalising suicide can often be traced back centuries with the earliest records showing ancient Roman efforts to prevent people dying by suicide through punitive measures. Religious and cultural influences have often been associated with laws and punishments towards those who attempt to end their lives, and on the families of those who die by suicide, including restrictions on burial rites and access to financial and other entitlements.

Despite the longevity of these laws and customs, there is now available greater knowledge, research evidence and community understanding that criminalisation does not deter suicide.

Laws and punitive measures fail to address the underlying issues of suicidal ideation, which are often rooted in mental health challenges, personal struggles with life circumstances, or societal pressures. By treating suicide as a crime, the focus on police and courts as the responses to suicidal people rather than providing these individuals with the necessary support they need to survive through the period of despair and stress.

In countries where suicide is considered a crime, families and friends of a person who has attempted suicide or died by suicide may face their own pressures, including stigma and discrimination. This discourages them from seeking help. It creates a climate of fear, secrecy, and stigma that ultimately hinders the mental health and wellbeing of many.

Decriminalisation to Enable Improved Suicide Prevention

It is therefore essential to work towards decriminalising suicide globally in order to reduce suicides.

LifeLine International views the decriminalisation of suicide as a key action to take to break down the barriers to help-seeking for those in crisis, so that every person, wherever they are can access vital crisis support services for suicide prevention.

Decriminalisation of suicide can be a catalyst for promoting and establishing crisis support services worldwide. These services can provide crucial assistance to individuals in moments of distress, helping them find the support they need and facilitating their journey towards mental health and well-being. At present, almost half a billion people worldwide, live in a nation where suicide is a crime, and lack access to free 24/7 crisis support services, highlighting the urgent need for change.

The recent wave of countries decriminalising suicide is a powerful signal of a revitalised approach to the prevention of suicide in many parts of the world, acknowledging that mental health is a universal human right and people experiencing a crisis deserve understanding, support, and care no matter who they are, where they are, or where they are from.

LifeLine International is leading a campaign, to identify and support movements for change and hope within countries where suicide remains a crime, or where the law is uncertain and ambiguous.

People In Crisis Die by Suicide

Suicides typically occur in those times when a person has reached a crisis state. These are times when intense emotions, high distress and deep despair overwhelm a person to the point that they are unable to cope; they are unable to make choices, decisions or even perform daily activities. The crisis state opens the door to self-harming and suicidal behaviour as an escape from unbearable pressure while it disrupts a person’s thought processes and disables their capabilities to stay safe.

A founder of crisis theory, Professor Gerard Caplan explained the dangers of the crisis state:

“The tension mounts beyond a further threshold or is burden increases over time to a breaking point. Major disorganisation of the individual with drastic results then occurs.”

A person with lived experience of crisis explained how it related to their suicide attempt:

“Abusive relationship for three years in the mid-2000s, took another three years to get out of. Next relationship also destructive. Work history patchy…workplaces have been chaotic (and) stressful, and short-term contracts have meant ongoing financial stress. This recent incident was preceded by high level of stress rather than suicidal ideation and wanting pain to stop rather than wanting to die.”

A person’s mental health is severely compromised during a crisis state. The person in a state of crisis is at that time likely to experience extremely high levels of psychological distress. The relationship between extreme levels of psychological distress and suicidal crisis-behaviour has been established in research literature. The interaction between distress, mental illness and suicidal behaviour is clear.

Suicides occur through a person seeking to escape a state of crisis. A leader of the field of suicidology, Professor Edwin Shneidman, used the term ‘psychache’ to describe the hurt, anguish, or ache, that takes of the mind of a person wishing to end their life. The person does not wish to die, but to escape the intensity of the suicidal crisis:

“Suicide happens when the psychache is deemed unbearable and death is actively sought to stop the unceasing flow of painful consciousness.”

A person with lived experience of wanting to die by provided this description of their underlying ambivalence about dying, alongside their wish to escape the severe pain and stress associated with their crisis:

“I remember it happened like, two years later, I found myself sort of standing there and you know, looking at looking over the bridge and, and I didn't know, I was certain that I was unlovable. And I was certain that there was nothing in life for me that I couldn't connect, and that I would never have that connection again. But somewhere there was just this doubt. Like, maybe there was this tiny voice of doubt, like maybe I was wrong, or maybe. And I remember I was standing there. And I had, I was decided I had this thought that I thought well, as bad as things are, it doesn't get any worse. If I still feel this way, I might as well just do it tomorrow. And I don't know where that came from, but just kept walking.”

The importance of reaching out to establish contact and communication with a person in crisis is illustrated in this person’s story:

“I told them that I'm sitting in the park on my own, and I'm gonna take my own life. The first part of the phone call was a little bit, a little bit blurry. Um, but the voice on that phone was such a caring person on that phone, who it almost felt like they were sitting beside me with their arm around me. That person on that phone wanted to talk to me, wanted to make me feel safe. And I could feel after a bit of time on the phone, that that person was genuine. And they really wanted to help. Having someone or knowing that someone who you are talking to is genuine and a genuine of wanting to help and wanting to, to reach out. That was a turning point for me going, I'm not alone. I can do this. There are people out there that do actually care. Um, it was that phone call was, it was, yeah, it was a life changer and a phone call that I'll never forget. Um, never forget.”

Laws that criminalise suicidal intent and behaviour, including suicide attempts, generally apply to people in crisis. This is shown in the behavioural indicators used to bring people to court and prosecution as shown in the below reported examples of people impacted by laws that criminalise suicide:

- Uganda: In 2013, a 22-year-old male was sentenced to 6 months imprisonment for attempted suicide. The male attempted to jump from the third floor of a building after the Uganda National Examination Board failed to release his exam results.

- Malawi: 2022 saw the case of a 41-year-old male that attempted suicide reach a mid-level appellate court, with the Court ultimately affirming the conviction. The attempt occurred immediately after he was exposed for selling goods he stole from his workplace.

Enforcement of laws that criminalise suicide is often left to the discretion of police, law officials and judges. Almost inevitably, it will be the behaviours and circumstances that people in crisis exhibit that will be signals used in this exercise of discretion; it will be the emotional outbursts of suicidal desires, expressions of despair and profound loss of hope for the future, or for improvement in life, self-injury behaviours which may or not be lethal, the explicit verbalisation of intent to kill oneself, the distress-related erratic behaviours, and self-destructive behavioural manifestations of a crisis state. These behaviours may also be associated with people experiencing elevated symptoms of mental illnesses such as psychosis or mood disorders.

- Bangladesh: 2019 News Report "The area is free from any kind of natural disasters—floods, river erosion, cyclones or tornadoes. People in this region have less capability to endure difficult conditions. They get emotional easily".

- Bahamas: 2021 Police Force Commissioner comments on men that attempted suicide after encountering relationship problems: “What I can tell you is that we had a few of those that we know were domestic related where the fellas are weak and they killed themselves because they were having issues with their females.”

More broadly, the factors surrounding suicidal behaviour and attempted suicides have been examined in several countries where laws criminalising suicide exist, demonstrating that the targets of the laws are people in a state of suicidal crisis.

A retrospective study of 22 individuals prosecuted for attempting suicide in Malaysia (prior to the decriminalisation of suicide law reforms) identified the traits of a crisis state surrounding expressions of suicidal intent and/or behaviour: nine cases were unemployed, six were divorced/separated; nine were reported as acting in response to negative life events. On examination by clinicians, five were found to have psychotic disorders, seven had mood disorders and four had substance use disorders. The authors of this study concluded:

“Suicides occur in complex situations and to people in heightened distress.”

Another study of 118 newspaper reported suicides in Nigeria identified factors like financial difficulties, marital problems, poor physical health, depression, drug abuse, and so on were found to have culminated in the suicide of the subjects. These people were in crisis – unable to cope with life difficulties and/or the impacts of mental illness. Their crisis issues are reflected in the profiles of callers to crisis support services throughout the world. The author concluded:

“There are underlying root causes of attempted suicide, including poverty/financial difficulties, unemployment, mental illness, physical illness, relationship and family difficulties, etc. Incarceration of attempted suicide does not address this situation and only has the effect of criminalizing mental illness, poverty and other causes of attempted suicide.”

People in crisis are responding to significant life stressors, emotions, and psychological distress. Often, the crisis state reflects the build-up of factors and circumstances over time culminating in an intense period where a person is unable to cope with more and becomes disabled and disrupted in their sense of being overwhelmed. Mental illness is often associated with a crisis state whether through the distortions of reality and perception, or through the unpleasantness of the symptoms. The suicidal crisis is a profound expression of human suffering.

It is unfair and unreasonable to target the person in crisis for criminal sanctions and punishment. Those in crisis are amongst those most in need of understanding, care, support, and practical assistance. It is their human right to mental health and to be protected from vulnerability to suicide. Decriminalisation of suicide through legal reforms and other measures will enable greater promotion of and access to vital crisis support services and pathways to meaningful mental health care.

An Alternative Approach – Provision of Crisis Support to Save Lives

Crisis intervention is focused on the prevention of injury or death from a suicidal crisis. It is at the time of crisis, that immediate contact is needed to de-escalate the heightened level of a person’s distress and interrupt the flow of destructive urges that facilitate actions through which a person may end their life, or severely injure themselves or others. The World Health Organization recommends the incorporation of crisis intervention in all suicide prevention strategies.

Religious outlooks also relate to the importance of crisis intervention to prevent loss of life or injury, as reflected in the outlooks of religious leaders in Ghana, one of the most religious countries in the world, that draw a connection between the imperative to avoid a person failing in their faith and dying a bad death by suicide with the importance of viewing religious faith as a protective factor, a support and a means by which distress and crisis can be alleviated:

“Thus, participants in the current study felt enjoined as religious leaders to act as frontline workers; they had a caring obligation or duty to help people in distress such as people in a suicidal crisis.”

Crisis support services provide an immediate response to people who are in crisis. Those who contact these services have often reached a point in their life where they cannot cope with life experiences or address problems that they face. They call seeking relief from stress and the comfort that contact with another person can bring. Family relationship breakdowns and conflicts, financial struggles, mental health conditions and their symptoms, exposure to violence and discrimination, alcohol and drug addictions, workplace difficulties, grief or loss, are typical of the experiences people contact crisis support services about.

There is an immediate and important effect from making that contact. The benefit of contacting a crisis support service is described in this person’s story:

“Sometimes all it takes when you want to die is a bit of distraction for a while, and then - the problem is still there, but the feelings of the desperation and wanting to be dead have evaporated again and you're back to - not happy, but you wouldn’t be dead for quids.”

The development of the telephone crisis lines was informed by research and clinical practice that identified the potential to reach people in crisis and intervene to prevent loss of life or self-harm:

“Organized suicide prevention efforts are based upon three sets of observations: (1) Suicidal behaviour tends to be associated with crises. These are life situations of special stress and limited temporal duration; (2) people consider suicide with great psychological ambivalence. Wishes to die or be killed exist simultaneously with and in conflict with wishes to be rescued and survive; (3) even in crises, people retain the human need to express themselves and communicate with others.”

Over the decades, researchers have built on the early studies of telephone crisis helplines with a systematic review of research literature reporting on the effectiveness of crisis support services to intervene during the time of a crisis in a person’s life, to reduce the intense stress and emotional pressure and to de-escalate the situation towards saving lives:

“The majority of studies showed beneficial impact on an immediate and intermediate degree of suicidal urgency, depressive mental states as well as positive feedback from users and counsellors."

LifeLine International is a network of Member organisations that provide crisis support services in 23 countries. Together with other crisis support service networks there are estimated to be more than 1,000 services worldwide reaching out to people. Every day, millions of people contact telephone helplines, crisis chat, and text services.

LifeLine International is motivated by compassion, respect for life and the relief of suffering to offer crisis support services to anyone. Like all crisis lines, and related crisis chat and text services, those operated by the Members of LifeLine International hold no barriers to use, no restrictions on a person’s background or situation. Crisis is a human experience that can impact on all persons. The universal provision of crisis support services may be regarded as an extension of every person’s right to mental health.

Law, Policy, Practice, and Variations

The laws reviewed for this Campaign Brief typically use terms such as “whoever attempts to commit suicide” or “attempts to kill himself” to identify who is to be found to have committed an offence or misdemeanour. Most laws specifically state that such persons are to be punished. Preparation or ideation to commit suicide is less clear across the laws reviewed with some including the person who “does any act towards the commission of such offence” while others exclude those who only show preparations for suicide such as writing a suicide note.

The various dimensions of the criminalisation of suicide, including common law offenses, statutory and regulatory provisions, religious law practices, variations across states within countries, discretionary enforcement of laws, and the resultant policy complications, are shown below.

Common Law Offenses

Suicide has been considered a crime in many countries, particularly in those with common law traditions dating back several centuries. Where common law provisions have remained unchecked/unchanged, these provisions remain current. Under such legal systems, taking one's own life is viewed as an offense against the state. Survivors of suicide attempts often face punitive measures, such as fines or imprisonment. The intention behind these laws is to deter individuals from self-harm or suicide.

Statutory and Regulatory Provisions

In addition to common law, some countries have codified the criminalisation of suicide in their statutory and regulatory frameworks. These provisions explicitly define suicide or suicide attempts as illegal acts and often prescribe specific penalties for those engaging in such actions.

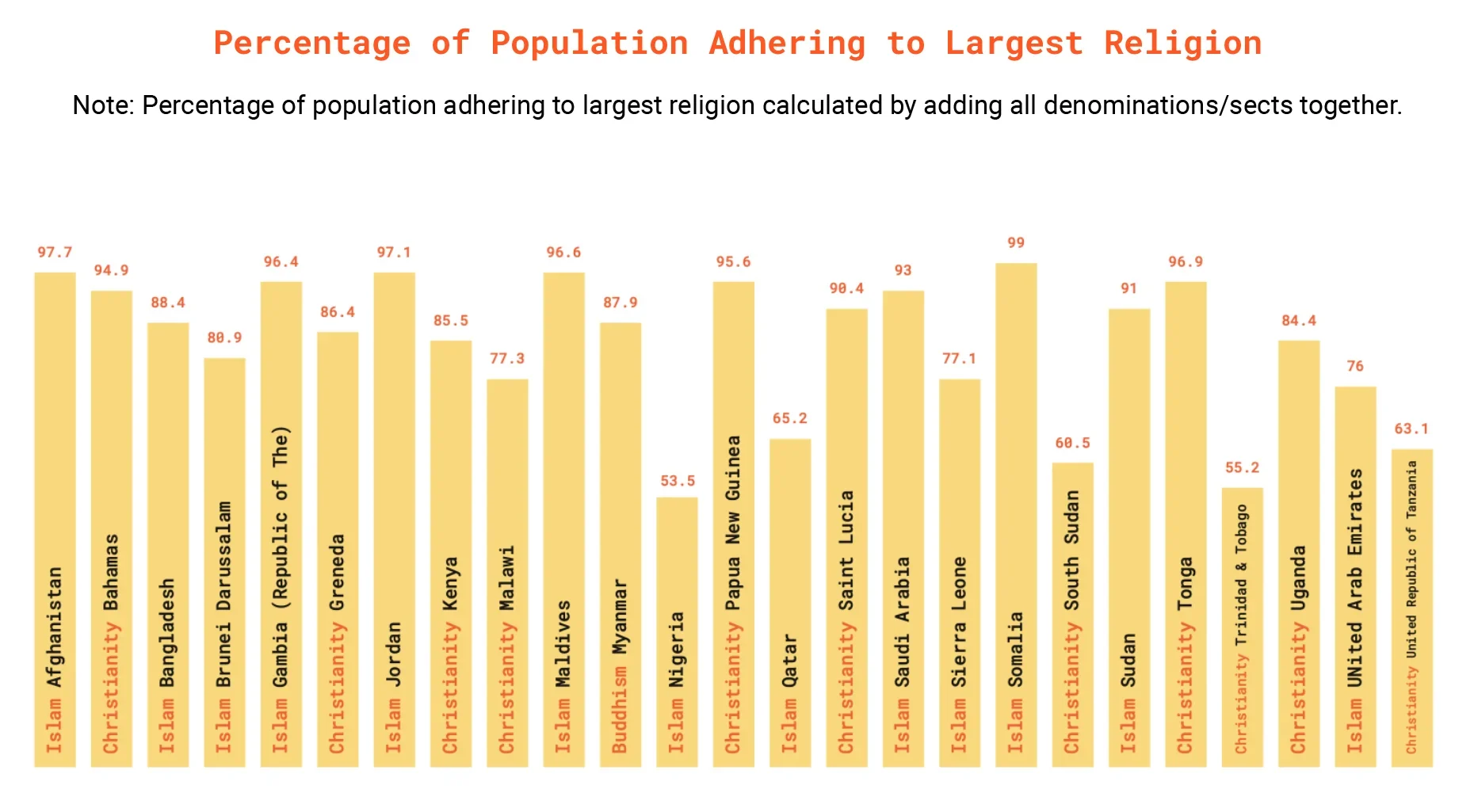

Religious Law Practices and Influence

Religious institutions and the religious laws that they uphold based on faith and beliefs can significantly shape a country's stance on suicide. In some nations, religious laws and doctrines are recognised by governments and their agents such as police and courts, so they directly influence the criminalisation of suicide. Certain religious teachings may stigmatise suicide as a sin or transgression against divine will, contributing to the continuation of punitive measures.

One example of the intersection of religious beliefs and suicide laws can be found in countries that recognise strict interpretations of Sharia law or conservative Christian doctrine. In these nations, suicide may be considered a crime, with consequences that align with religious teachings. This interplay between religious beliefs, cultural practices, and legal frameworks creates a complex landscape for individuals in crisis, adding a layer of spiritual condemnation to their struggles.

Cultural and Social Attitudes Towards Suicide

Intricate cultural, traditional, and religious beliefs can profoundly shape a nation’s understanding and responses towards suicide, as often found in African countries with long histories of social, religious and cultural development. Some communities and cultures view suicide through a lens of malevolence, associating it with malevolent spirits that demand appeasement through rituals. Religious influences add complexity, as some teachings label suicide as a sin or transgression against divine will, further contributing to stigma and fear surrounding the topic.

Addressing these challenges requires culturally sensitive approaches that provide alternatives while respecting traditions. Rather than confronting cultural and religious norms head-on, collaborative and respectful engagement with communities is vital to fostering change.

Variations Across States within Countries

In federated nations, or countries with highly decentralised governmental structures, the criminalisation of suicide may vary significantly from one state or province to another. This decentralised approach results in a complex legal landscape where individuals within the same country may face different consequences for suicide attempts based on their geographic location.

For example, in the United States, suicide laws vary from state to state often based on historic precedent such as the common law. While some states have decriminalised suicide attempts and focused on mental health support, others may still retain punitive measures due to unclear provisions on the influence on common law. Nigeria and Brazil, enormous federal states, have other diverse political, cultural and historical circumstances giving rise to different legal practice in different states. This level of research is however out of the scope of this Brief.

'Discretionary' Enforcement of Laws

In countries where suicide is criminalised, the enforcement of these laws can be inconsistent. Law enforcement agencies and judicial bodies may exercise discretion in pursuing legal action against individuals who attempt suicide. This discretionary approach means that not all individuals in crisis face legal consequences, but it can also result in unequal treatment under the law.

Policy Contradictions

Laws and regulations criminalising suicide are counterproductive to global efforts to reduce suicide rates. These laws foster stigma, fear, and shame around mental health issues, preventing individuals from seeking help during moments of acute crisis.

These laws also hinder the collection of accurate suicide-related data, hampering evidence-based policy responses. When suicide attempts are treated as criminal acts, people may be less likely to report incidents, leading to underreporting and a lack of understanding of the true scale of the problem.

The existence of laws criminalising suicide complicates the development of comprehensive national suicide prevention strategies. Governments may hesitate to allocate resources to mental health services and suicide prevention services, or community action, when such efforts are seen as conflicting with existing legal frameworks.

Addressing the decriminalisation of suicide requires collaboration among various stakeholders, including governments, policymakers, health systems, criminal justice systems, civil society organisations, religious and community leaders, and individuals with lived experiences. The move towards decriminalisation is a critical step in promoting mental health as a universal human right, reducing stigma surrounding help seeking in times of personal crisis, and facilitating effective suicide prevention strategies. Decriminalisation of suicide aligns with the global commitment to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goal 3.4.2, which seeks to reduce suicide rates as part of the broader effort to improve mental health and well-being worldwide.

The Global Situation

Snapshot:

- 25 Countries where suicide is a crime - a aggregate population of 850 million where suicide prevention resources are extremely limited if available at all and help-seeking almost impossible.

- 27 Countries where the legal status of suicide is unclear – an aggregate population of some 370 million people.

- Together, more than 1.2 billion people, in 52 countries – a quarter of the world’s nations, have legal system that either criminalise suicide directly, or are hostile to crisis support and help-seeking.

Clarifying and changing these laws will save lives.

Countries With Laws Against Attempted Suicide or Recent Prosecutions

At least 25 countries have laws against attempted suicide or have recently sought to prosecute individuals for attempted suicide. These countries include:

- Afghanistan

- Bahamas – Penal Code, section 309

- Bangladesh – Penal Code, section 309

- Brunei Darussalam – Penal Code, article 309 & Syariah Penal Code Order 2013, section 165

- Gambia (Republic of The) – Criminal Code Act, section 206

- Grenada – Criminal Code, section 233

- Jordan – Penal Code

- Kenya – Penal Code, section 226

- Malawi – Penal Code, section 229

- Maldives – Penal Code

- Myanmar – Penal Code, section 309

- Nigeria – Criminal Code, section 237 & Penal Code, section 231

- Papua New Guinea – Criminal Code Act, section 311

- Qatar – Penal Code, article 304

- Saint Lucia – Criminal Code, section 94

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- Somalia – Penal Code, article 437

- South Sudan – Penal Code 2008, section 215

- Sudan – Penal Code, section 261

- Tonga – Criminal Offences Act 1926, section 100

- Trinidad & Tobago

- Uganda – Penal Code, section 210

- United Arab Emirates – Penal Code, article 335

- United Republic of Tanzania – Penal Code, section 217

By naming countries where recent prosecutions for attempted suicide have occurred, this Campaign Brief differs from previous endeavours in this area. In some cases, the legal basis for these prosecutions or charges is difficult to ascertain – however prosecutions speak for themselves. The prosecution or charging of individuals for attempted suicide, even if occurring on questionable legal grounds, further restricts help seeking from those in crisis situations by creating a potentially unfounded fear of legal sanction.

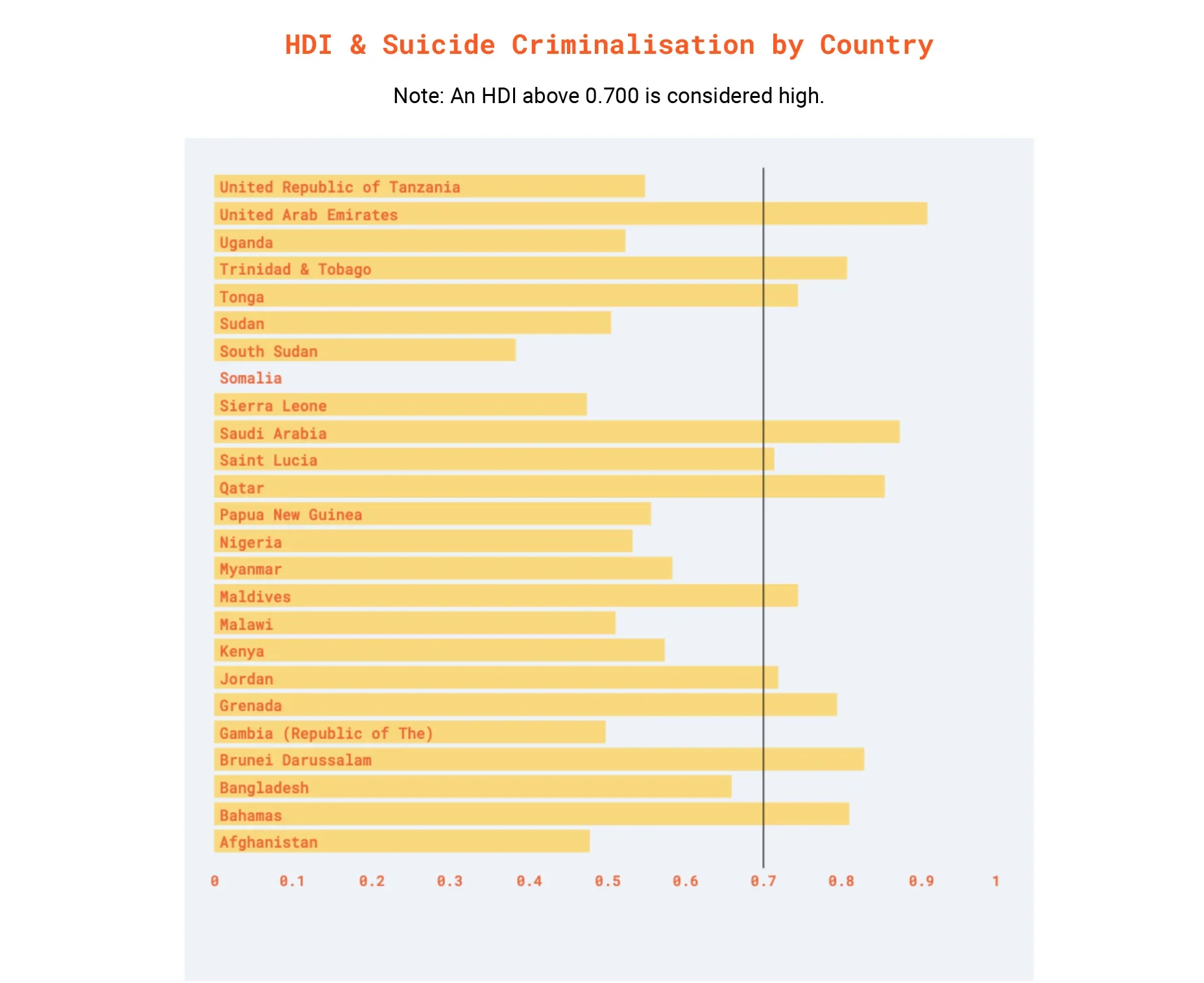

Most countries that criminalise suicide also identify as low- or middle-income countries. Of the countries with known laws against attempted suicide, or a history of recent prosecutions, over half have a Human Development Index score below 0.700. This means they fall into the low or medium categories of the Human Development Index. This highlights that laws against attempted suicide often occur in nations where mental health support is the least available. Therefore, the burden of dealing with those in states of crisis may be wholly placed on the criminal justice system, a task it is not equipped for, and does not perform well in.

Countries with Uncertain or Unknown Legal Frameworks

The review of laws, evidence and information undertaken for this Campaign Brief has been unable to ascertain the legal status of attempted suicide in 27 countries. Countries with uncertain or unknown legal frameworks toward attempted suicide include:

- Algeria

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Barbados

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Djibouti

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eritrea

- Eswatini

- Haiti

- Iran (Islamic Republic of)

- Jamaica

- Kuwait

- Lebanon

- Libya

- Madagascar

- Mali

- Mauritania

- Mauritius

- Morocco

- Namibia

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Senegal

- Suriname

- Togo

- Tunisia

- Yemen

This uncertainty can generally be attributed to the following factors:

- In many of the countries in question, open access to updated and official English language versions of legislation have been difficult to attain. In some nations, even if official versions of legislation are published, legislation databases are rarely updated or incomplete. This makes an accurate assessment of attempted suicide laws challenging.

- The application of common law offences in some nations has been difficult to clarify. This has created uncertainty as to what extent the common law offence of attempted suicide may exist in a country. Common law offences are an obscure area of the law that exists in common law countries, and this obscurity often leads to a distinct lack of resources.

- In some countries, credible information has been obtained suggesting attempted suicide is criminalised, or that prosecutions for attempted suicide still occur. Despite this helpful information, LifeLine International have been unable to verify the claims with certainty.

- Conflicting information regarding the status of attempted suicide has been received from some countries.

- The role of uncodified laws in some countries, alongside the influence of religious or traditional laws have rendered it difficult to ascertain a complete picture of the legal attitudes toward attempted suicide.

Whilst the legal status of attempted suicide in these countries remains unclear, it should not be assumed that because of this uncertainty, attempted suicide is criminalised. Inquiries will continue through next steps to clarify the status of attempted suicide laws in these countries, by consulting local lawyers and engaging with relevant governments. The Campaign will provide opportunities through which knowledge surrounding laws can be shared, leveraging local expertise to build a clearer picture of laws relating to attempted suicide.

It is important to address situations in countries where there are unclear or confusing provisions. Ensuring individuals have clear knowledge of legal frameworks that decriminalise suicide plays a vital role in encouraging help seeking from those in crisis situations, by allaying their fears of any legal repercussions.

For example: Nepal provides an illustration of the importance of legal clarity. There is a commonly held impression in this country that attempted suicide is illegal, despite the fact it appears to have never been a crime. This false impression of illegality does not only continue to stigmatise conversations around suicide, but also reduces help seeking behaviour and the reporting of such incidents.

Comparing our findings to previous reports

This Campaign Brief both acknowledges the helpful and informed contributions by the World Health Organisation, the International Association of Suicide Prevention, and United for Global Mental Health, and also highlights a few departures from findings in previously developed reports, as outlined below.

This Brief remains supplementary to these previous findings and should be read in addition to the body of work developed by these and other leading global organisations.

| UGMH Report (2021) | Notes | WHO List (Sept 2023) | LLI List (Oct 2023) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | |||

| Bahamas | Bahamas | Bahamas | |

| Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Bangladesh | |

| Brunei | Brunei | Brunei | |

| Gambia | Gambia | ||

| Ghana | Since Decriminalised | ||

| Guyana | Since Decriminalised | ||

| Grenada | Grenada | ||

| India | Since Decriminalised | India | |

| Jordan | Jordan | ||

| Kenya | Kenya | Kenya | |

| Malawi | Malawi | Malawi | |

| Maldives | Maldives | ||

| Malaysia | Since Decriminalised | ||

| Myanmar | Myanmar | Myanmar | |

| Nigeria | Nigeria | Nigeria | |

| Pakistan | Since Decriminalised | ||

| Papua New Guinea | Papua New Guinea | Papua New Guinea | |

| Qatar | Qatar | Qatar | |

| Saint Lucia | Saint Lucia | Saint Lucia | |

| Saudi Arabia | Saudi Arabia | ||

| Sierra Leone | Sierra Leone | ||

| Somalia | Somalia | Somalia | |

| South Sudan | South Sudan | South Sudan | |

| Sudan | Sudan | Sudan | |

| Tanzania | Tanzania | Tanzania | |

| Tonga | Tonga | Tonga | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | |||

| Uganda | Uganda | Uganda | |

| United Arab Emirates | United Arab Emirates |

Positive Impact of The Decriminalisation of Suicide: Case Studies

The decriminalisation of suicide is a global movement for change that reflects a shift in society's understanding of suicide, mental health and the importance of providing compassionate and effective responses to those in crisis.

Five case studies of countries that have recently decriminalised suicide have been examined: Ghana, Guyana, Malaysia, Singapore and Pakistan. Common themes regarding the positive impact of decriminalisation of suicide have been identified: legislative change, policy improvements, mental health care, national suicide prevention strategies, crisis support services, and community action and local support. These case studies offer valuable insights into the transformative power of legislative reform and the collaborative efforts of stakeholders in promoting mental well-being and suicide safe communities.

Common themes across each country

Historical Context and Colonial Legacy:

- All five case studies highlight the historical context of colonial-era laws that treated suicide as a criminal offense.

- These laws perpetuated stigma and hindered the provision of appropriate mental health support.

- Decriminalisation represents a break from colonial thinking and a recognition that punitive measures do not address the underlying mental health issues and personal crises driving individuals to attempt suicide.

Legislative Reform:

- In each case, legislative reform played a pivotal role in decriminalising suicide.

- Amendments to criminal codes and penal laws shifted the focus from punishment to understanding and support.

- The legislative changes marked a profound shift towards viewing suicide as a mental health issue rather than a criminal act.

- Advocacy and Stakeholders:

- Advocates of mental health in these countries, including mental health workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and human rights peaks, played a crucial role in pushing for decriminalisation.

- Collaborative efforts brought together diverse stakeholders, including government officials, medical professionals, clinicians, legal experts, and civil society organisations, to help drive change.

- These collaborative efforts by a diverse range of stakeholders are, perhaps, the most important part of any country’s decriminalisation efforts.

- Policy Improvements:

- The decriminalisation of suicide prompted a shift in policies towards mental health care and support.

- Governments considered initiatives like national suicide prevention policies, mental health helplines, and awareness campaigns to reduce stigma and promote help-seeking behaviour.

- Mental Health Acts:

- Decriminalisation opened the door to better mental health care in these countries, with efforts to improve logistics, facilities, and resources for mental health support.

- Organisations dedicated to suicide prevention worked on programs and awareness campaigns targeting educators and the general public.

- Crisis Support Services:

- The changes in legislation also led to the expansion of crisis response teams and helplines.

- Suicide prevention and mental health organisations received funding from the mental health budgets to bolster community-based services, ensuring timely intervention for those in crisis.

- Community Impact:

- The decriminalisation of suicide was welcomed by the public and mental health professionals in these countries.

- It fostered a more compassionate and understanding approach to mental health, greatly reducing stigma and encouraging help-seeking behaviours.

Case Studies – in brief

Guyana:

- The comprehensive Suicide Prevention Bill in Guyana represented a significant move towards improving mental health care across the country.

- Historical colonial-era laws were replaced by legislation that focused on suicide prevention services, support for survivors, and the establishment of a National Suicide Prevention Commission.

- Advocacy efforts and collaborative initiatives paved the way for a more compassionate and empathetic approach to mental health.

Malaysia:

- Malaysia's journey towards decriminalisation highlighted the need for a collaborative approach involving international experts, mental health advocacy groups, government officials, and healthcare professionals.

- The legislative reforms not only abolished outdated colonial-era laws but also demonstrated a commitment to prioritising crisis intervention, treatment, rehabilitation, and support over punishment.

- Malaysia's experience showcases the transformative power of collective action in addressing mental health challenges.

Pakistan:

- Pakistan's decriminalisation of suicide marked a milestone for mental health and human rights.

- Advocacy groups, international health organisations, mental health professionals, legal experts, and government officials collaborated to bring about legislative change.

- The reforms opened the door to policy improvements, amendments to mental health acts, crisis support expansion, and a shift towards a more compassionate and empathetic society.

Singapore:

- Singapore's decriminalisation of suicide represented a profound shift in societal attitudes towards mental health.

- Advocacy groups like Silver Ribbon Singapore, AWARE, and the Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) played instrumental roles in raising awareness and dismantling stigma.

- The legislative reform paved the way for a more compassionate approach, emphasising crisis support and mental health assistance.

Ghana:

- Ghana's decision to decriminalise suicide marked a significant victory in the drive for mental health recognition and support.

- The legislative reform inspired policy changes, mental health care improvements, crisis support expansion, and community acceptance.

- Ghana's experience demonstrates the positive impact of decriminalisation on a national level, emphasising the importance of collaboration among stakeholders.

Overall Findings

The decriminalisation of suicide has had a positive impact on legislative change, policy improvements, mental health acts, national suicide prevention strategies, crisis support services, and community across multiple countries. These case studies demonstrate that collaborative efforts among diverse stakeholders, including advocacy groups, government officials, healthcare professionals, and the community, are essential in bringing about transformative change in mental health policy and practice. Decriminalisation serves as a powerful symbol of society's commitment to prioritising mental well-being and compassion over punishment, ultimately contributing to a more resilient and empathetic world.

Detailed case studies can be found on www.suicide-decrim.network - our Knowledge Management Platform for actors for change.

The Start of Something: A Global Campaign to Decriminalise Suicide

A campaign advancing our mission: more services, helping more people, in more places.

In 2023, LifeLine International is initiating ‘Decriminalise Suicide Worldwide’ - a global campaign that will aim to work across the 52 identified countries to destigmatise help seeking by increasing the understanding of suicide prevention and ensuring the establishment of readily available crisis support services across the world. In many cases, decriminalisation of suicide will address one of the most significant barriers to achieving this - criminal sanction.

In 25 nations, we have already identified specific legislation that requires amendment. We aim to work with individuals and organisations in countries where suicide remains a crime, to advocate for meaningful legislative change. Through legislative changes and the establishment or enhancement of crisis support and suicide prevention services, we seek to support these local actors committed to preventing suicide, saving lives, and offer hope to those in distress.

In countries where decriminalisation of suicide is underway, or has recently occurred, positive developments include crisis support systems expanding, helplines being enhanced, community health capability being built, and mental health budgets considered for allocation to community organisations. While decriminalisation is not a panacea, it stands as a testament to progressive change, offering a glimmer of hope for individuals who experience a crisis.

LifeLine International believes in the importance and effectiveness of crisis support services, like those delivered by our Members. They are the lifelines that bridge the gap between despair and hope, offering immediate assistance to those in their darkest hours. Crisis lines provide a critical touchpoint in the journey towards mental health. They offer a compassionate ear, a non-judgmental space, and a source of comfort for individuals in crisis. This becomes even more effective after decriminalisation, as individuals feel safer to reach out without fear of repercussions.

As countries progress towards decriminalisation, LifeLine International stands ready to play a leading role in this transformation. These services offer a space where individuals can disclose their struggles openly and seek the support of others during their darkest moments, drawing on the foundation of empathy and understanding.

LifeLine International's Members’ digital capability is of paramount importance to this, as it highlights the availability of crisis support services, to those in crisis, regardless of their geographical location. For example, through national toll fee crisis lines – or through preferred modality – voice, chat, text, or social media for example.

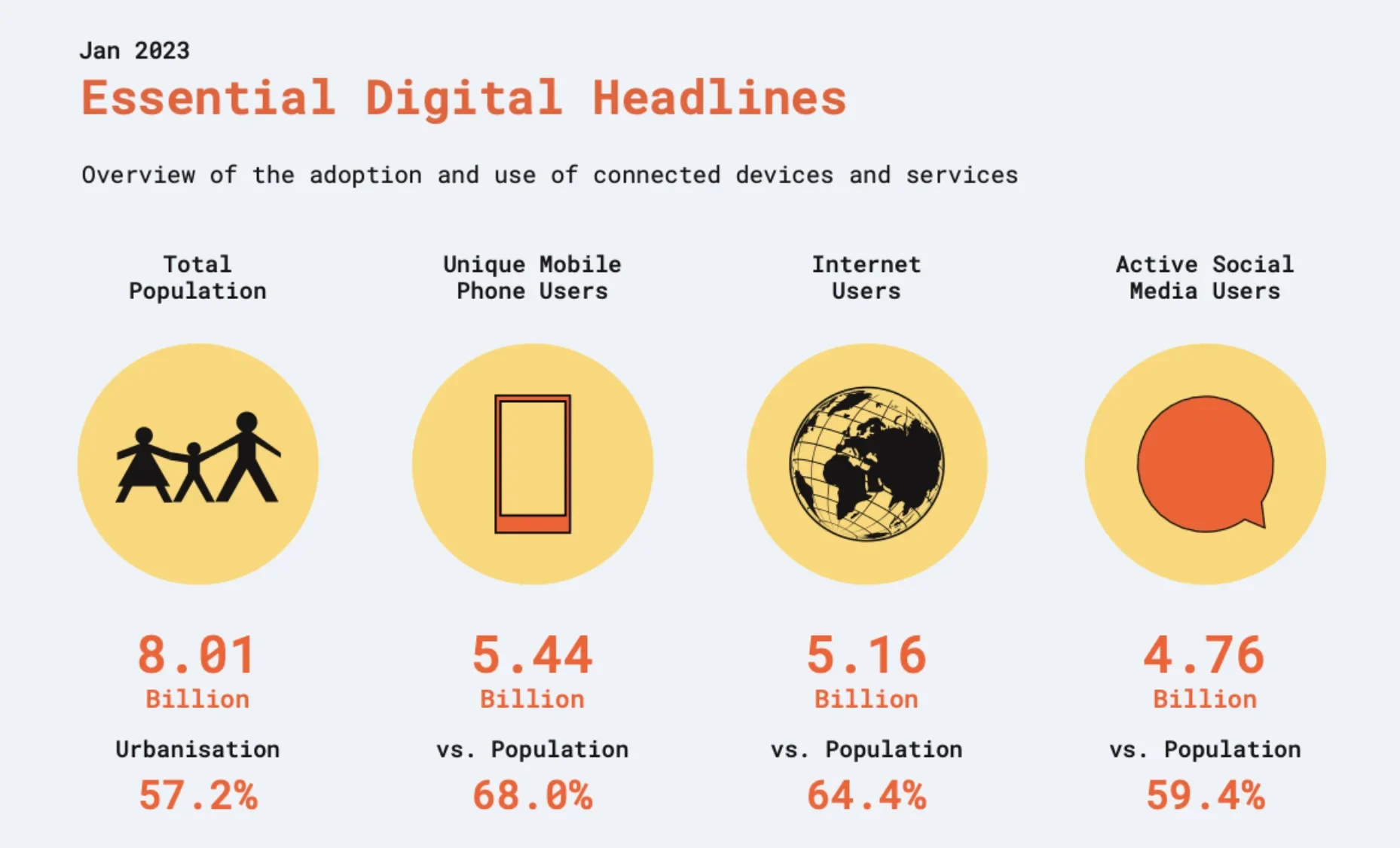

In a world where connectivity has become increasingly the norm, our ability to extend a lifeline through phone lines and the internet is better than ever. With 5.44 billion people owning mobile phones and 5.16 billion having access to the internet, according to We Are Social's 2023 digital report, our digital presence ensures that we can reach a vast proportion of the global population. This accessibility means that, at any given moment, millions of people facing emotional distress or crises can connect with vital support and resources, at the time they need it, transcending borders and time zones. It amplifies our mission to prioritise mental health and provide assistance to those in need, regardless of where they are in the world.

Sources: United Nations; Government bodies; GSMA Intelligence; ITU; World Bank; Eurostat; CNNIC; APJII; IAMAI & Kantar; CIA World Factbook; Company Advertising Resources and Earnings Report; OCDH; Beta Research Center; Kepios Analysis. Advisory: Social media users may not represent unique individuals. Comparability: Significant revisions to source data, including comprehensive revisions to population data. Figures are not comparable with previous reports. All figures use the latest available data, but some source data may not have been updated in the past year. See notes on data for full details.

As more countries join this movement to decriminalise suicide, a new global chapter is being written - one that prioritises mental health as an essential part of human well-being and a universal human right. The union of decriminalisation and crisis support is not just about legal change, it's a testament to humanity's collective commitment to lifting each other up in times of need.

Decriminalise Suicide Worldwide – the Campaign

The campaign to decriminalise suicide is designed on a simple idea – to empower and connect supporters of change with empowered and connected actors for change.

We know from LifeLine International’s current Membership base alone, there is a large international volunteer-enabled online-active community of individuals who care deeply about suicide prevention and decriminalisation. We will engage and build this community through a digital online social change campaign. We call them our supporters for change.

But to be effective, change must be locally driven. We also know that national decriminalisation campaigns succeed with the right combination of actors for change – civil society, legislators, clinicians, help centres operators, mental health charities, government ministries and NGOs, together with committed individuals and volunteers, many of whom have lived experience.

These actors for change, across the 52 counties, will be engaged through a bespoke Knowledge Management Platform (KMP) that will put all of LifeLine International’s know-how around decriminalisation and subsequent service set up, at the service of validated local coalitions. The KMP will also provide the means by which coalitions can form and define how LifeLine International call assist them on their decriminalisation journeys.

Adding international voices to national campaigns can be impactful – notably when and where those national campaigns request this support. Through the creativity of the online platform we will build this capability – matching supporters of change with actors for change for greatest impact.

Each year, LifeLine International will work in close focus with up to three countries where decriminalisation campaigns are advancing against a number of criteria. The KMP also provides the means for an annual call for support from local coalitions to define how LifeLine International could support their national campaigns.

Decriminalise Suicide Worldwide will be powered by two digital platforms.

www.25crimes.org – The Community Campaign Platform for Supporters of Change -

Working through the campaign website, www.25crimes.org, supporters will be provided information and collateral and content designed to empower them to engage in soft global advocacy. These resources include information, digital assets and materials, and messaging that enable will individuals to raise awareness and support the cause of decriminalising suicide on a global scale, and on an individual basis.

www.suicide-decrim.network – The Knowledge Management Platform for Actors for Change

Meanwhile, for individuals and organisations that have capacity and capability to be part of an on-the-ground movement, www.suicide-decrim.network becomes a dynamic engagement platform that provides a comprehensive range of materials and content tailored to the unique needs of each campaign and movement for change, in each individual country. These in-country campaigns are primarily focused on advocating for changes in legislation related to suicide decriminalisation or clarifying unclear legal frameworks. This dynamic platform will not only provide actors for change with the materials they need, but guidance and connection, to assist with building a local case for change.

The platform’s role is central to the functions of the campaign:

- Data Hub: the platform hosts a repository of the most important global resources available, including academic thinking and case studies, examples of legislation, messaging and campaign collateral resource, as a guide and inspire actors for change.

- Country profiling and microsites for coordinated action: Each of the 52 countries will have a microsite which is pre-populated with critical data on suicide prevention, criminal or legal status, creating a localised repository of knowledge, while collecting and organising country specific information. This information is then easily accessible to campaigners and advocates and help create awareness and understanding of the state of play per country and build momentum through a guided process of change.

- Self-management of activity, content and data: the platform’s content creation tools enable LifeLine International and actors for change to develop compelling narratives, materials, and messages relevant to unique countries. These resources are distributed to appropriate target groups and audiences, ensuring that each campaign receives content that resonates with its unique context.

- Impact Measurement: The platform also goes beyond content creation and knowledge sharing, allowing actors for change and LifeLine International to measure the impact of their efforts, both globally and locally, and their direct progress towards achieving global targets, like the UN’s Sustainment Management Goal 3.4.2. This data-driven approach helps campaigns adapt and refine their strategies for maximum effectiveness, while growing a network of trusted experts and insights and building authoritative data sets and sources. We will track our progress to impact over years at national, regional and systems change levels.

A strong and unifying campaign identity

LifeLine International has designed this campaign to be inclusive. We welcome participation and support at every level. To ensure this, we have developed a specific campaign branding to encourage its use and dissemination by campaign partners of every sort – from global NGOs to nationally based community groups. Our Brandmark, of diminishing gaol bars, is a powerful icon and call to action.

An eco-system approach for campaign longevity and impact.

We aim to work in partnership at every level:

Sector Participants - we share our position statements and operational intent with our sector peers and partners, with other operators, policy and research leaders, and NGOs with whom we share fundamental value alignment such as human rights, to engage a broad range of informed and expert participants.

Stakeholders – our campaign provides the infrastructure and network building capability to engage with key stakeholders necessary to drive reform and validate change across the 52 countries.

Supporters – our online social change community platform helps us collect and share critical voices in support of change through online creativity linking support and action – the means to deliver and activate our calls to action.

Service Provision Partners – where we campaign to change the law, we will support new, enhanced or extended crisis helplines services – either through a LifeLine International Members or with an operating partner – to drive the lifesaving impact crisis support services can provide.

About LifeLine International

LifeLine International is a global organisation representing 27 Members, in 23 separate countries. Our Members operate over 200 suicide prevention and crisis support services across the world. Our shared mission is to create a world where quality suicide prevention support is available, accepted, and encouraged.

Our goal is to ensure that the life-saving work of our Members is fully recognised, valued, and supported, especially as more countries develop National Suicide Prevention strategies in line with World Health Organisation guidelines.

We focus on supporting the expansion of community-based crisis support services, operated by our Members and beyond. We believe that crisis support services must be accessible and widely promoted in all communities, regardless of location, cultural practice or legal frameworks. We fundamentally believe that they play a critical role in the overall continuum of care for suicide prevention.

Our ultimate beneficiaries are help seekers – individuals in extreme distress and despair and at risk of suicide.

www.lifeline-international.com

Reports on Criminalisation of Suicide and Other References

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8860012/

https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanpsy/PIIS2215-0366(23)00057-3.pdf

https://newsroom.gy/2022/11/08/national-assembly-approves-suicide-prevention-bill/

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)01176-5/fulltext

https://time.com/6290858/malaysia-suicide-decriminalization-mental-health/

https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/05/23/attempted-suicide-no-longer-a-crime

https://www.dawn.com/news/1780259

https://360info.org/with-suicide-no-longer-a-crime-the-real-work-begins/

https://voicepk.net/2022/12/suicide-attempts-finally-decriminalised-in-pakistan/

https://tribune.com.pk/story/2392477/law-penalising-suicide-attempts-abolished

https://www.silverribbonsingapore.com/advocacyforchange.html

https://www.sos.org.sg/blog/attempted-suicide-is-no-longer-a-crime-in-singapore

https://www.aware.org.sg/wp-content/uploads/Distress-is-not-a-crime-final-report.pdf

https://www.trtafrika.com/insight/mental-health-what-ghanas-suicide-decriminalisation-means-13598735

https://www.trtafrika.com/africa/attempted-suicide-no-longer-a-crime-in-ghana-13527273

https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/ghana-decriminalizes-attempted-suicide.html